The interview below originally appeared in the January/February 2005 edition of the bilingual London bulletin, Voice of Nor Serount (pages 36 to 39).

An Interview with Markar Melkonian,

Author of My Brother's Road

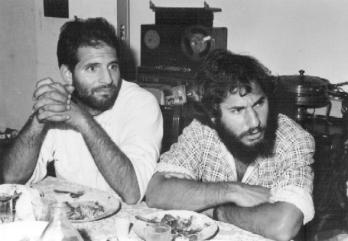

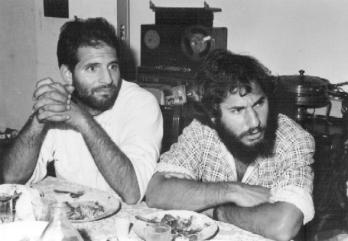

Following his book launch at the Hayashen Center's Monte Melkonian Hall on February 27, 2005, The Voice of Nor Serount London could not miss the opportunity of interviewing the brother of National Hero and freedom-fighter Monte Melkonian who was martyred at the end of the Nagorno Karabagh conflict. Here is Markar Melkonian’s interview conducted by Manuel Atamian, in Armenian and later translated into English.

Voice of Nor Serount: The London publishing house I.B. Tauris is coming out with your book, My Brother’s Road. Please tell us something about the book’s contents.

Markar: My Brother`s Road is a biography/memoir about my late brother, Monte Melkonian. Monte was a third-generation Central California boy who abandoned a promising career as an archaeologist to become an Armenian militant. He was a witness to revolution in Iran, an Armenian militiaman in Beirut, an “armed propagandist” in Europe, a guerrilla fighter in southern Lebanon, a prison strike leader in France, and finally, a commander of 4000 fighters and thirty tanks in Mountainous Karabagh. He died in battle on June 12, 1993, and has since been designated a national hero of Armenia. My Brother’s Road traces the long journey of his short life.

Voice of Nor Serount: Could you tell us something about your family’s history, in brief? When did your predecessors (your parents or your grandparents) immigrate to America, and from whence?

Markar: Our father’s father was a shepherd and a bonded labourer from Kharatsor, a small village near Kharpert. His name was Ghazar. His wife, my paternal grandmother Haiganoush, was a village girl from an impoverished peasant family. In 1913, Ghazar, his wife, and the two of their five children who had not already died of tuberculosis sought asylum on a French ship and made their way to the United States. They became farm labourers in Fresno County, where my father was born.

My maternal grandfather, Misak, was from the town of Marsovan (today’s Merzifon), near the Black Sea town of Samsun, in Turkey. He was from an urbanized petty bourgeois family, but they were economically vulnerable. In his late teens and early twenties, Misak became active in the Hunchakian Party. Ottoman authorities imprisoned him at least twice, and he was ordered to leave the country of his birth. He was lucky to escape with his life. Eventually, he ended up in Fresno County, where he became a small farmer and raised a family. Our mother was his only daughter. |

|

Monte never knew either of his grandfathers; they both died years before he was born. The only grandparent Monte could remember was our grandmother Jemima. Her parents brought her from Marsovan to Fresno in 1883, when she was three years old, but her extended family had already settled there years earlier. Our maternal great granduncle, Jacob Seropian, was one of the first Armenians to purchase land in Fresno County, California. That was in the late 1870’s, back when California was at the end of the western frontier. Cattle rustlers and train robbers hid out in the foothills to the east of town. Years later, in the 1890’s, Jacob’s half brothers, John and George, helped break the monopoly of the hated Southern Pacific Railroad in the San Joaquin Valley. I describe this incident in Chapter Three of My Brother’s Road. As a child, Monte watched a television drama entitled “Six Wagons to the Sea,” which was based on this episode. Fresno native Albert Bezzerides, the screenwriter for the film noir classic, Kiss Me Deadly, wrote the screenplay.

Voice of Nor Serount: My Brother’s Road is a biography, the story of the road Monte travelled. Please tell us something about your brother’s adolescence and his school and university days.

Markar: Monte was a bright student, a good baseball player, swimmer and runner, and the first elected president of his elementary school. He was a tough kid, too, the first one to dive off the highest rock into the river. At the age of fifteen, he went to Japan and stayed with friends there for a year. He studied the language and history of Japan, as well as karate and kendo, Japanese classical sword fighting. He visited Vietnam just before its liberation, and stayed for a short while in a Buddhist monastery near Seoul, Korea, where the abbot presented him with a robe and a Buddhist name. This, too, was part of his formal education.

Monte entered the University of California at Berkeley in fall 1975 as a Regents Scholar, with a double major in history and mathematics. He was impatient to graduate from university early, so he soon switched to a major of his own design, in Ancient Asian History and Archaeology. In the summer of 1977, when Monte was not yet twenty years old, he joined an archaeological field party in the Nevada desert, excavating Northern Paiute and Panamint Shoshone artefacts.

Monte earned money for college by working at odd jobs, applying for academic scholarships, and taking trips to Burma and the Thai-Cambodian border to buy rubies for buyers in the United States. He completed his undergraduate studies in less than three years, wrote his honours thesis on Urartuan rock-cut tombs, and was accepted for graduate work at Oxford University. As things turned out, though, he never attended Oxford. Instead, he re-enrolled in the school of life, the school of struggle and resistance.

|

I should mention that Armenian was Monte’s fourth or fifth language. His second language was Spanish, and his third language was Japanese. He studied French and Turkish before he learned Armenian, and he also spoke passable Italian, conversational Arabic, and a few words of Farsi and Kurdish.

Voice of Nor Serount: Monte was a native-born American, raised and educated in an American environment. Within Monte’s inner life, when and under what conditions did he wake up spiritually, to become the exceptional, selfless patriot that we know him as?

Markar: I suppose the closest thing to a dramatic awakening of Armenian patriotism in Monte took place on June 12, 1970, when our family paid a brief visit to our mother’s ancestral town of Merzifon. Monte saw the church where his great grandfather had been buried. It had been converted into a cinema house, and was festooned with movie posters. He also stood on the street and stared at a house that had belonged his mother’s side of the family before the genocide. Chapter Two of My Brother’s Road consists in large part of a description of this visit.

|

But I doubt that Monte ever really had a sudden dramatic realization that he was Armenian—whatever that may involve. Remember, we were products of small town Cold War America. Like our playmates and classmates, we were imbued with the assumption that America, One Nation under (or perhaps even over) God, was an exceptional nation on a divine mission to uplift the world. We learned that Yankees, not Armenians, were God’s Chosen People. Somewhere along the line, however, Monte grew tired of American exceptionalism. Perhaps it was when he learned that the Yokut Indians of our San Joaquin Valley had not evaporated like dew, but had been annihilated in a “war of extermination,” as California Governor Peter H. Burnette called it in 1851. In any case, by his mid-teens, Monte had enough brains and enough experience to have figured out that most people on earth were disenfranchised and downtrodden. And that included Armenians.

Monte loved the unique things of Armenian culture, of course—music, architecture, poetry, proverbs, and food. But in adulthood, he used to say Menk normal jhoghovoortmun enk, “We’re a normal people.” Fellow Armenians have misunderstood Monte when it came to his love of things Armenian. By identifying himself as an Armenian first, Monte never thought he was thereby enrolling in a peculiarly gifted and cosmically oppressed tribe. On the contrary, by embracing an Armenian identity, Monte was consciously rejecting the notion of a Chosen People, and aligning himself with the majority human population of planet Earth in the twentieth century.

People have asked me how it was that Monte, a Cub Scout, grew up to become an Armenian militant? When I’ve attempted to answer this question, I’ve pointed out that people are different, that even as a child Monte was daring, stubborn, curious, and smart. I’ve pointed out that Monte’s character combined a high esteem for mathematics and historical accuracy with a relentless will to confront and overcome adversity. I’ve described the role that family history, travel, and book learning played in his intellectual development. But to be honest, none of these responses have really satisfied me. I’ve never been able to come up with a satisfactory off-the-cuff response to the most frequent question people ask about my brother. So I’ve concluded that the only way to answer this question properly is to tell a complete story about Monte’s life. My Brother’s Road is a 300-page answer to the question How did Monte become who he became?

|

|

Voice of Nor Serount: In the course of researching your book, what sources did you use, aside from your own personal recollections and the testimonies of family members?

Markar: On my website, www.mybrothersroad.com, I’ve included a long bibliography organized by chapter and topic. But this bibliography represents only a fraction of the published sources I consulted in the course of researching this book, and the published sources in turn represent only a small fraction of all the sources I consulted.

It took me seven years and three months to research and write this book, and another year to prepare the manuscript for publication. Over the course of these years, Monte’s widow Seta and I have conducted hundreds of interviews in four or five languages. My colleague Myriam Gaume succeeded in obtaining legal documents in Paris, and after many years of repeated requests through the Freedom of Information Act, I finally succeeded in receiving a pile of documents on Monte from the U.S. State Department and the FBI. One of the most important sources of information for the last half of the book was Seta herself. Like her late husband, she has an incredible memory for details. I am fortunate to have had Seta as a collaborator on this book.

Voice of Nor Serount: When you presented My Brother’s Road at the Monte Melkonian Hall at London’s Hayashen Center on February 27, you came up with such vivid descriptions that one would think that you yourself had retraced the same journey as Monte, but as a writer. If you have indeed made the same journey, when did your journey take place? Were there surprises? Were there difficulties? Focus, if you would, on Nagorno Karabagh.

Markar: Thank you for the kind words. Between June 1993 and June 2003, I made several research trips to Nagorno Karabagh. But no, I did not follow my brother’s journey in those mountains. Not even in my role as a writer. My visits to Nagorno Karabagh have been brief, pleasant, and mostly calm. Thanks to the hospitality of the good people of Martuni, neither I nor my parents or my sisters have encountered any difficulties worth mentioning. Monte’s years in the mountains of Karabagh, by contrast, were a tornado of fire and shrapnel. If I’ve been able to describe the last years of his life convincingly, then I have Seta to thank, as well as many generous interview subjects (and perhaps my experiences with wars in other places).

Nagorno Karabagh was full of surprises. It is a surprisingly beautiful land with surprisingly generous people. But perhaps the biggest surprise was realizing the enormity of the challenges that my brother faced as a military commander in Martuni. I describe some of those challenges in the final chapters of My Brother’s Road.

Voice of Nor Serount: Did you always agree with Monte’s bold, risky plans? As his older brother, did you try to keep him away from dangerous operations, or did you encourage him from the sidelines?

Markar: Monte and I were not always on the same page when it came to his plans and actions. Even before he had joined ASALA, he had plans—or perhaps ideas or feelings more nebulous than plans--that vexed me. In Chapters Five and Six of My Brother’s Road, I describe several such “plans”: a military training camp in the village of Ainjar; some sort of kamikaze operation against an unspecified Turkish target; a putsch against the local Armenian leadership in east Beirut, and so on. On the occasions when I found out about such “plans” in time, I tried my best to talk Monte out of them.

|

|

We had differences of opinion. Even as a feisty youth, I never entirely believed that the dream of liberating western Armenia was practicable. B y the late 1980’s, when it had become clear that the Soviet Union had already died in everything but name, my last faint hopes for “border rectifications” with Turkey flickered out. Monte and I discussed this at length. He acknowledged that the imperialists’ victory in the Cold War had even further compromised Armenia’s prospects for regaining Kars and Ardahan, but I don’t think he ever entirely gave up his hope for “border rectifications” with Turkey.

Voice of Nor Serount: What do you see as a permanent solution for the conflict in Nagorno Karabagh? Is it possible to imagine a sort of solution that Monte would have resolutely opposed if he had lived?

Markar: I’ve always agreed with my brother that the pivotal question in Nagorno Karabagh is the question of self-determination. The sovereignty of established borders, in Monte’s opinion, is secondary at best. This is as true of Nagorno Karabagh as it is of Chechnya and Kurdistan. I would like to have seen the peoples of Nagorno Karabagh—the Armenian majority, as well as the Azeri minority and others--determine their own future peacefully. It’s too late for this, of course, but there might still be a point in emphasizing that some of us were not cheerleaders for war in Nagorno Karabagh.

I don’t know what will happen in Nagorno Karabagh, and I will not pretend to predict the future. On the one hand, the people of Nagorno Karabagh say with one voice that they will never allow their land to fall under Baku’s control again. On the other hand, Azeri leaders and the leaders of what is euphemistically called the International Community, tell us with supreme confidence that it is only a matter of time before Baku regains control over Nagorno Karabagh. Regional and international players have their own agendas, and the economic, diplomatic, and military balance of power in the region is in flux. I wouldn’t trust anyone who claims to know what the outcome of this conflict will be.

What sort of outcome would Monte have resolutely opposed? Well, he would not have wanted Baku to regain control over Nagorno Karabagh, ever. That much is certain.

It should be said, however, that over the course of the past dozen years many things have come to pass that Monte would not have liked. Many things. If he had lived to see Armenia today, in its present condition of poverty, depopulation, corruption, and diplomatic servility, he would have lived too long. Monte loved Armenia deeply. He was fortunate not to have lived to see the full consequences of Armenia’s return to the capitalist fold.

|

|

Voice of Nor Serount: We’ve heard of the existence of the Monte Melkonian Fund. Could you tell us something about that fund and its mission?

Markar: The Monte Melkonian Fund, Inc. is a California 501(c)(3) tax-deductible charity dedicated to helping the neediest of the needy in Armenia. The Fund provides support to under-funded schools, hospitals, and clinics that serve refugees and victims of war, especially children. We work with our sister organization in Yerevan, The Monte Melkonian Benevolent Association. More information about the Fund and its projects is available at: www.melkonian.org.

Voice of Nor Serount: Thank you for your answers.

Markar: Thank you. Hachoghootyoon (trans.: Good luck.).